Harshaw Road outside of Patagonia begins with good gravel and is lined with ranches and horses by Kathy Alexander.

The area southwest of Patagonia, Arizona, to the Mexican border, is lined with ghost towns and mining remnants speaking to more prosperous days. Patagonia, 18 miles northeast of Nogales on Highway 82, is a small town of fewer than 1,000 souls that attracts art enthusiasts and nature lovers today.

Before you start a trip along the back roads to the ghost towns of Harshaw, Mowry, Washington Camp, Duquesne, and Lochiel, fill up your tank before you arrive in Patagonia, as we could find only one open gas station, and its hours are limited. There is a small market in town where you should stock up on water and snacks before taking what could be an all-day trip.

While the road out of Patagonia is good gravel because of the many ranches in the area, it deteriorates the farther you move southward, and a high clearance vehicle is recommended.

Beware that this area is rife with illegal aliens and, as such, also U.S. Border Patrol. When we visited, we were stopped for a vehicle check (lots of things can hide in an SUV.) But, we also learned from the Border Patrol Officer that most tourists do not generally frequent these back roads because it is also a favored route for drug smugglers. It could be a dangerous place for a day trip.

Heading to the first ghost town along this path, Harshaw, you will turn off State Route 82 in Patagonia onto Taylor Avenue, travel one block, and turn east onto Harshaw Road. Harshaw lies about 8 miles southeast of Patagonia.

Harshaw

In 1877, a rancher named David Harshaw was grazing cattle in this area when he discovered a tremendously rich silver vein. In no time, the rancher-turned-miner called his “find” Hermosa, and people began to flock to the area. The town that sprang up around the mine was named for him.

The mine, located due south of Harshaw up a Jeep trail, became the primary producer in the area, peaking at more than 350,000 in ore during a four-month period in 1880. However, by this time, David Harshaw had sold the claim and moved on. The town, however, boomed with some 2,000 people, of which 150 worked at the mine and another 20 at the stamp mill. A post office was established on April 29, 1880. The camp boasted seven saloons, a boarding house, a hotel, various shops, and a newspaper called the Arizona Bullion on its bustling mile-long Main Street.

But for Harshaw, its boomtown life would be short. In 1882, the town suffered a fire and a dramatic drop in the quality of the ore, and the majority of the population moved on. The Tombstone Epitaph reported that same year that “over 200 buildings stand empty with broken windows and open doors.”

However, in 1887, Harshaw would see a minor rebirth when a Tucson man named James Finley purchased the Hermosa claim for $600. Finley soon revived the mining, but on a smaller scale. The town then had about 100 people. In 1903, two events occurred to kill the town again – Finley died, and the market price of silver dropped significantly. Its post office was discontinued forever on March 4, 1903.

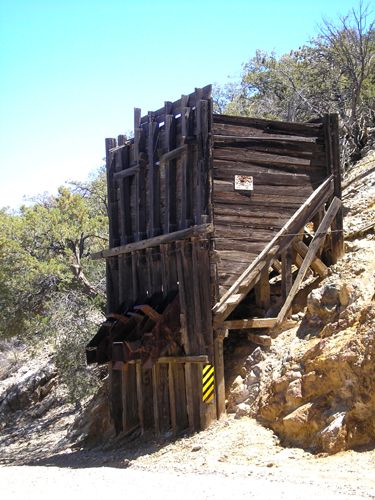

Abandoned again in 1937, the Arizona Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO) reopened the nearby Flux and Trench Mines, bringing a few residents back to the area. Asarco continued mining in the area until 1956.

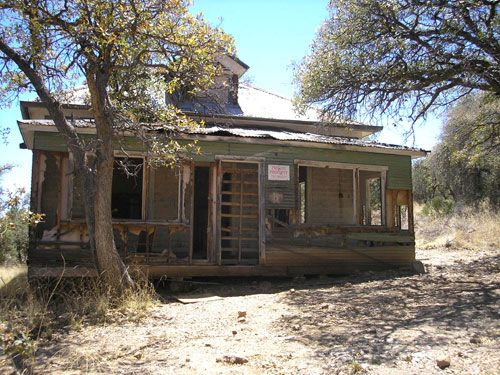

Today, there are just a few remnants left of this old community, including the James Finley home, a tin-roofed adobe residence that is still occupied, a crumbling home, and the cemetery. Just south of the site is the remains of the Harshaw/Trench Camp Church and mining remnants.

Mowry

Continuing on the same road, now called FR 49, another five miles or so is the old town site of Mowry. The site is .2 miles east on FR214; however, we could not find any remains other than a few low foundations.

Mining here dates back to 1857 when Mexicans worked it. However, in 1859, the claim was bought by Sylvester Mowry and renamed the Mowry Mine. Investing heavily in equipment, the mine began to produce so successfully that it would ship some $1.5 million in ore over the next several years.

Rolling in the dough and happy at this investment, Mowry’s bright future would suddenly end in 1862 when he was arrested and charged with selling lead for ammunition to the Confederacy. He was sent to Yuma Prison, his mine was sold, and his equipment destroyed. Later that same year, he was released for lack of evidence and tried to get the government to reimburse him and return the mine. However, he was unsuccessful and moved on to England, where he died in 1871 at the age of 39. Though the mine was allegedly producing more than $4,000 per week during the time of its seizure, it only worked sporadically afterward as it passed through several hands and never again made a profit.

Though we were only able to find, a few foundation remains at the townsite, a rugged road that goes north off FR 214, leading to some adobe walls which continue to stand. Beyond them are said to be the mine and smelter site, the collapsed shaft, and a stone powder house. However, this area is on private property, so we did not venture down any of the roads that ventured north.

Washington Camp

Another four miles south, just beyond the junction of FR 49 and Duquesne Road, is the old site of Washington Camp, once the largest community south of Patagonia. Serving as a supply community for the mining towns of Duquesne, Mowry, and Harshaw, prospecting occurred only briefly in the early 1860s but was quickly abandoned due to numerous Apache attacks. However, in 1890, when the Duquesne Mining and Reduction Company began operations, the town of Duquesne was born, as well as nearby Washington Camp, which housed the reduction plant, miners’ bunkhouses, a general store, and a school. The town grew to some 1,000 residents.

Today, some old mining buildings, shafts, and tailings can still be seen.

Duquesne

Just another half mile down the road (which is now FR 61), the ghost town enthusiast will be rewarded with many more remains in the old mining camp of Duquesne (pronounced doo-kane). So close to Washington Camp, one wonders why they were called separate “towns.” To reach the main buildings, take FR 128, a rough road that branches to the right from FR 61 and eventually circles back.

When the Duquesne Mining and Reduction Company began operations here in the late 1880s, they laid out the city where the company official’s residences and mining offices would be. A post office began on May 13, 1880. Duquesne grew to include 1,000 residents and several businesses.

This old town features numerous old homes, the mining company headquarters, and foundations. According to the locals, tourists are not welcome here; in fact, this is where we got stopped by the Border Patrol. The area is heavily posted, with no trespassing signs. However, the road is a public forest road, and most remains can be photographed from the road.

Continuing on, the road will circle back around until it returns to FR 61. Another four miles south is a monument to Fray Marcos de Niza, a Franciscan friar and the first European to enter the United States west of the Rocky Mountains.

Just southeast of the monument is Lochiel.

Lochiel

This old town was first called Luttrell, named for Dr. J.M. Luttrell, who ran a boarding house and owned the Holland Company Smelting Works. The first post office opened with the name Luttrell in 1880. For unknown reasons, another post office opened in 1882, called La Noria, just a mile from the first post office. A year later, they both closed. However, another opened in 1884, with the town’s “final” name of Lochiel. Named for two brothers for the ancestral home in Scotland, this time, the name stuck. The mining community grew to include two smelters, three saloons, five stores, a boarding house, several businesses, and a population of about 400. Though the miners profited, the ranchers were at risk during the early days, as none other than Pancho Villa would often come across the border to steal cattle before escaping back to Mexico.

But, like most mining towns, its life was short, and its post office closed forever on September 30, 1911. However, there was still life in Lochiel, and in 1918; a one-room schoolhouse and a teacherage still exist today. In fact, in the 1980s, the town wanted to re-open the school and had several applications from teachers interested in the challenge of a one-room schoolhouse. Unfortunately, there were no students to attend. During this same decade, the customs station serving border crossings was also closed for budgetary reasons.

This old community, nestled in the corner of the San Rafael Valley and surrounded by cottonwoods is an oasis in the desert, so much so that several Hollywood films have been made here, including Monte Walsh, Oklahoma!, and Tom Horn.

The town is also privately owned and fenced off, but several buildings, including the church, the old U.S. Customs Station, the one-room schoolhouse, and teacherage, can all be seen from the road.

Our journey then took us another 20 miles northeast to the ghost town of Sunnyside, Arizona. An interesting place with a fascinating history. See more HERE!

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

See our Santa Cruz County Ghost Towns gallery HERE

Also See: