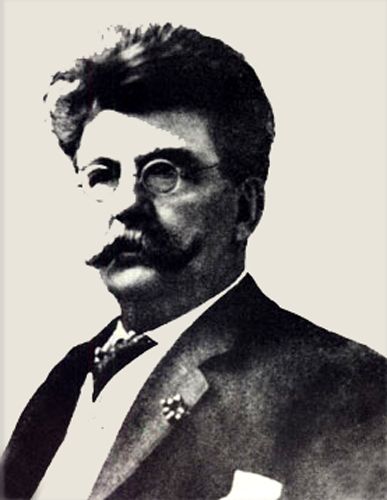

Francis “Borax” Smith, touch of color by LOA.

Francis Marion Smith, known as the “Borax King” and “Frank,” was a Death Valley mining magnate and businessman who headed the Pacific Coast Borax Company. Born in Richmond, Wisconsin, on February 2, 1846, to Henry G. and Charlotte Paul Smith, Francis attended public schools as a child before graduating from Milton College in Wisconsin.

At the age of 21, he left his father’s ranch and, answering the irresistible call of the West, made his way toward the Pacific, visiting Idaho, California, and Nevada. He spent considerable time in mining and other work in those states before settling in Nevada for five years.

In the late 1860s, Smith worked under a contract with several ore mills near Columbus, Nevada, locating and obtaining timber for the various mining camps. While working at Teel’s Marsh, he discovered a rich supply of borax. He collected samples and had them assayed, which proved the ore to be higher than any known sources of borax. He soon staked several claims and began his career as a borax miner.

With the help of his older brother, Julius, and two brothers named Storey, the men established a borax works at the edge of the marsh to concentrate the borax crystals and separate them from dirt and other impurities. Operations began in 1873 under the name Smith and Storey Brothers Borax Co. Later, the Smiths acquired the Storey brothers’ interest, and the company name was changed to Smith Brothers Borax Co. and later to Teel’s Marsh Borax Co. The Teel’s Marsh deposits soon became the world’s principal supply source and remained so for years, bringing borax to wide commercial use worldwide.

In 1875, during a national depression, Smith opened a retail store and office at 185 Wall Street in New York City to expand the borax market. His advertising claims that borax would “clean black cashmere, cameos, and coral, keep milk and cream sweet” and “prevent diphtheria, lung fever, and kidney trouble” may have been exaggerated. Still, they helped popularize the cleaning additive in a prime market when sales slumped. That same year, Francis married Mary “Mollie” Rebecca Thompson Wright, a Brooklyn, New York divorcee.

In 1877, Smith founded the settlement of Marietta, Nevada, now a semi-ghost town, from which the borax was shipped in a 30-ton load using two large wagons with a third wagon for food and water drawn by a 24-mule team for 160 miles across the Great Basin Desert from Marietta to Wadsworth, Nevada where the nearest Central Pacific Railroad siding was.

In 1881, Smith and his wife, Mollie, moved to Oakland, California, where Frank began to invest in real estate while continuing his operations at Teel’s Marsh, Nevada. In 1884, Smith bought out his brother’s interest in their partnership, and Frank began to turn his eye to potential development in Death Valley. When William T. Coleman, who owned the Harmony and Amargosa Borax Works, the Lila C Mine, the Furnace Creek Ranch, and other properties in Death Valley, California, began to have financial troubles in the late 1880s, Smith provided Coleman with the capital in exchange for mortgages on the property.

In 1889, to expand the processing of raw minerals that formed the borax product, Smith worked with renowned engineer and reinforced concrete innovator Ernest L. Ransome to design two new refineries for him—one in West Alameda, California, and the other in Bayonne, New Jersey. The California refinery was recognized for being the first structure of its kind to be built with reinforced concrete.

Boraxo

Unfortunately for William T. Coleman, his empire collapsed, and Smith gained all his properties in 1890. The name of Smith’s properties then became the Pacific Coast Borax Company. Smith ceased operations at the Harmony and Amargosa Borax Works to focus on mining operations at Borate, California, in the Calico Mountains. Initially, the ore was hand sorted at the mine and hauled to Daggett, California, using the 20 mule teams and wagons that William T. Coleman had first used in Death Valley.

In 1891, Stephen Mather, the administrator of the company’s New York office, persuaded Smith to add the name 20 Mule Team Borax to go with the famous sketch of the mule team already on the box. The trademark would be registered three years later. Mather would go on to own the Thorkildsen-Mather Borax Compan, and in 1916, was appointed the first Director of the new National Park Service.

While Frank was busy with his borax interests, his wife was busy with charity work — especially working hard for aid and assistance for orphaned girls. Mollie, after a tragic miscarriage, could never have children of her own, but she yearned for them. Raising money for their assistance, the couple also took in several young girls as wards over the years. In 1883, they adopted an infant girl who they named Marion Francis Smith. Ten years later, they would take in two young teenagers named Anna Mae and Sarah Winifred Burdge. While there were many others they looked after, these three would become part of the “Solid Six,” as Frank affectionately called them. Over the years, Mollie’s contributions and assistance to these many girls would continue.

The Smith’s Presdeleau estate on Shelter Island in New York.

In 1892, Frank and Mollie went east to Shelter Island, New York, to find a place to build a summer home. This was probably for two reasons, the first of which was that New York was Mollie’s original home, and the second, Shelter Island was also the place where his friend and soon-to-be partner, Frank Havens, already had a summer home. Before they left New York, they had purchased a 42-acre homestead, which already included a colonial-style home. Frank then hired an architect to add to the original home, which would eventually feature 35 rooms. He also added significant acreage over the years until the estate sat amid some 435 acres. They called their new summer retreat “Presdeleau.” Over the next several years, Frank would continue to buy more property in the area, adding to the estate.

Convinced there was a more efficient and profitable way to haul the ore from the mines to the railhead at Daggett, Frank began experimenting with a steam tractor called “Old Dinah” in 1894. Unfortunately, due to the roads from the mines, the experiment failed, and he continued to utilize the 20-mule teams for the next several years.

In the meantime, Smith had also been investing heavily in real estate and public transit in Oakland. He, along with partner Frank Havens, formed the Realty Syndicate in 1895, buying area real estate and acquiring and consolidating a number of small, independent transit companies to create an integrated system of streetcar lines and rail extensions to a number of subdivisions the company was developing.

The same year, a mansion was completed for the Smiths in Oakland, California. Frank had acquired an estate of some 53 acres in the previous few years, and his wife, Mollie, oversaw the planning and building of a new mansion. Designed by famed architect Walter J. Mathews, Frank set out immediately to acquire additional property, and soon, the mansion was surrounded by 53 acres, where tame deer and peacocks roamed freely. Called Arbor Villa, the 42-room mansion sat on a hilltop east of Lake Merritt off of Park Boulevard. Filled with luxurious furnishings and art, including a pipe organ, the mansion featured a ballroom and a bowling alley for the many guests the Smiths often entertained. Over the next decade, Mollie would often open her homes in Oakland and Shelter Island, New York, for charity-raising events, entertaining as many as 5,000 people at once. A year later, Mollie would hire Evelyn Kate Ellis, one of the very girls she had helped through the years, as her assistant. Evelyn would later become Frank’s second wife.

With beautiful homes on both the West Coast and the East Coast, the family split their time between the two locations, spending the summers, from June through October, at Presdeleau. With their Chinese staff and maids, the family would board Frank’s private railroad car, Hauoli, and an additional Pullman from Oakland, California, to Jersey City, New Jersey. From there, they would transfer to Smith’s personal steam yacht, also called Hauoli, and make their way down Long Island Sound to Smith’s Cove, where they would step ashore at Presdeleau. Along with Frank and Mollie, their girls also accompanied them. They now included Charlotte Grace Sperry, who they took in in 1895, a girl named Florence Nightingale, and Evelyn Kate Ellis, Mollie’s secretary.

In 1896, Frank and Ernest L. Ransome built a concrete Ferry Building in San Francisco that would become an integral part of the Realty Syndicate transportation system that he and Frank Havens owned. Soon after, Smith and Ransome established the Ransome Concrete Machinery Company of Dunellen, New Jersey, which would secure several patents over the next several years and pave the way for modern-day concrete construction.

In 1898, Frank constructed the 12-mile-long narrow gauge Borate & Daggett Railroad. The ore was then shipped to a calcining plant located at Marion, just North of Daggett. This allowed a better grade of ore to be shipped to Alameda via the Southern Pacific Railroad. At that time, the 20 mule teams were retired, but the “brand” would continue to be used.

In the meantime, Mollie was still actively pursuing her charity work for orphaned girls and wished to expand. To accommodate her wishes, Frank gave her 30 acres of land for a Christmas present, which would be converted into the Mary R. Smith Trust and build, over the years, nine cottages to house these orphaned girls. Governed by a board of trustees of women of the First Congregational Church, the first cottage was built in 1901. Housing girls aged 4 – 25 years old in need of a home were allowed to stay as long as necessary. Each cottage had a house mother selected by Mollie Smith, who directed them to provide as close to a normal home life as possible. The girls were instructed to make most of their own clothes and help with the housework. All of the girls attended public schools, and many grew up attending college. Many of the cottages were named for the children that Mollie had adopted and cared for. In addition to the home, a social hall called the Home Club was also built.

Tragically, however, Mollie died of a stroke on December 31, 1905. A year and a half later, in June 1907, Frank married Evelyn Kate Ellis, Mary’s secretary, who was also her choice of a second wife should anything happen to her. Over the next six years, the couple would have four children.

In the same year that Frank married Evelyn, it became obvious that the mining days at Borate, California, were numbered. The main operations were shifted to the previously undeveloped Lila C Mine at old Ryan, near Death Valley. All the equipment, including the buildings, was removed and sent to the Lila C, leaving Borate bare. Again, long mule teams were used in the early years while Smith constructed the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Pacific Coast Borax Company, connecting with the Southern Pacific Railroad across the Mojave River and Kelso Dunes at Ludlow, California.

Also, in 1907, Frank C. Havens and Smith’s Realty Syndicate opened the Key Route Inn, a major hotel in Oakland that served the Key Route transit system. Opening on May 7, 1907, it straddled what is now Grand Avenue along the west side of Broadway. The inn was a massive wood-framed structure with open timbering, and one of its most remarkable features was the large archway and corridor through which the tracks of one of the Key Route’s transbay lines passed. In this corridor was a stop connected to the hotel’s main lobby.

Life in the Smith household continued as it had before, with the family spending the summer in New York with the children. Frank’s second wife, Evelyn, also continued with Mollie’s philanthropic work, becoming the president of the Mary R. Smith Trust, holding very close to the founder’s plans.

In 1913, Smith, like William T. Coleman before him, became financially overextended and had to turn over most of his assets to creditors who refused to extend new loans. He lost his borax mines, company, land, transit investments, private railroad cars, and boats. An effort was also made to take away his homes, but because the properties had been deeded to Evelyn, the family could keep them. They did not make their annual trek to Shelter Island for the first time in several years.

Francis Marion Smith, 1907.

Though Frank was financially strapped, the Pacific Coast Borax Company continued without him, as Smith worked hard to rebuild his fortune. Before his financial downfall, he had helped Ben Edwards develop a silver mine in Tonopah, Nevada. He formed the Tonopah Extension Mining and Milling Company, which later became the West End Consolidated Mining Company.

The rewards for his help resulted in Frank owning a sizable number of shares in the company, which he had placed in Evelyn’s name. When these shares also came under the scrutiny of his creditors, Frank filed a lawsuit to protect his wife’s interests and won.

He then used his West End capital for new projects, including acquiring mineral rights to a large section of Searles Lake in the Searles Valley in northern San Bernardino County, California. However, it would be years before he would make a profit.

Luck turned for Frank in 1921 with the discovery of the richest colemanite deposit, then known, near the village of St. Thomas, Nevada. Frank made a bid against his former company — the Pacific Coast Borax Company, for the claim and won. His engineers determined that the grade and quality of the ore were unbelievably rich and estimated that the value was from 10 to 60 million dollars. Frank named it the Anniversary Mine, as the claims were acquired on the anniversary of his marriage to his second wife. The Anniversary Mine would operate from 1922 to 1928.

The profits from this claim provided the capital to develop the Searles Lake deposits when a young chemist, Henry Helmers, discovered a profitable process for refining the lake brines into marketable products. He then formed the West End Chemical Company and built the company town of Trona, California, and the Trona Railway, a short-line railroad, to ship the products to the Union Pacific Railroad connection at Searles, California.

However, his creditors had not been entirely paid, and in February 1922, 530 acres of his land in New York, as well as his farm tools and horses, were slated to be sold. The family was able to retain the household goods and furnishings, as these were said to have been the property of Evelyn Smith.

As Frank continued to use the profits of the West End Consolidated Mining Company, which ran the silver mine in Nevada, to purchase more claims, it angered shareholders and resulted in lawsuits. In 1926, this resulted in his departure from the company, but he still continued to own the West End Chemical Company, which was still profitable.

By 1928, Frank was 82 years old, and stress was taking its toll. He began to suffer a series of small strokes and was forced to relinquish control of West End Chemical Company. His manager, John Sherman, then took over, aided by Evelyn and her younger brother, George C. Ellis. At that time, Frank and Evelyn also moved from their Oakland mansion into a smaller residence across Lake Merritt in the Adams Point neighborhood. They also sold off several large pieces of the estate’s gardens, upon which several modest homes were built. They also tried to sell their mansion, but no buyer could be found after the stock market crash of 1929.

By 1930, Frank had lost the ability to speak, though his mind remained clear. The barn and lookout tower at their New York home burned down the same year. The very same year, the Key Route Inn in Oakland, which Frank had helped to build, also suffered major damage from a fire.

On August 27, 1931, Francis Marion Smith died at age 85. He is buried in Oakland’s Mountain View Cemetery along “Millionaires Row.” After his death, Smith’s hillside property was subdivided into lots, and as part of this redevelopment, the mansion was demolished in 1932. However, before the mansion fell under the wrecking ball, many of the marketable fixtures and furnishings were sold. That same year, the Key Route Inn, also suffering from the Great Depression, was torn down 25 years after it opened.

Also in 1932, Evelyn took over as president of the West End Chemical Company, which she managed for several years before turning it over to her brother George. The cottages under the Mary R. Smith Trust continued to be used for several decades. However, when the State took over providing for orphans, the Mary R. Smith Trust funds were redirected to providing nursing education for qualified young women. The cottages were then sold. Four of them still stand today.

Evelyn Smith retained the Shelter Island property. However, by 1938, it had become terribly run down; after a hurricane damaged it so badly, Evelyn had it torn down. Later, Frank and Evelyn’s daughter, Dorothy Smith Bayley, built a house on one of the subdivided lots on Smith Cove and raised her children there during the summers. She died in October 2002, and the property was sold. However, a Smith legacy still survives on Shelter Island—a Japanese-style bridge built of concrete.

Evelyn died in California on June 8, 1957.

As to Smith’s West End Chemical Company, it still operates today. In 1956, it merged with Stauffer Chemical Company, and in 1974, it was purchased by Kerr-McGee, which built a $175 million Argus soda ash plant in 1978. The North American Chemical Corporation purchased the chemical plant in 1990. It was leased at Searles Lake from the Bureau of Land Management up until they sold the Plant in December 1998 to IMC Global. In 2004, Sun Capital Investments LLC acquired all of the IMC Chemicals facilities in Searles Valley, which were renamed Searles Valley Minerals, Inc., which continues the operation of the plant and railroad.

Smith’s railroad in Oakland continued, becoming the “B” transbay line upon the opening of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge railway. The “B” bus route replaced the rail line in April 1958 and was subsequently incorporated into the publicly owned AC Transit system.

After Smith lost control of the Pacific Coast Borax Company, the business continued working at the Lila C Mine until it finally played out in 1914. They then moved “Old Ryan” to the site of what was then called Devair or Colemanite to the northwest, working several borax mines. The new town was also called Ryan. The company also constructed a$400,000 concentration mill at Death Valley Junction. Establishing a town, they built what is now known as the Amargosa Hotel and Amargosa Opera House. In 1926, they also built the Furnace Creek Inn.

Rio Tinto open-pit Borax Mine in Boron, California.

While still running the Pacific Coast Borax Company, Smith purchased the boric acid mineral rights at the “Suckow claims” at Boron, California, between Barstow and Mojave. Though never developed by Smith’s Pacific Coast Borax Compan, his corporate successors have obtained all their borax minerals from the Suckow claims for over 75 years. They estimated that the remaining deposits would last for nearly as long. It is now California’s largest open-pit mine, the world’s largest borax mine. In 1956, the Pacific Coast Borax Company merged with United States Potash Corporation to form U.S. Borax, which itself was acquired by the Rio Tinto Group in 1967. As a wholly-owned subsidiary, the company is now known as Rio Tinto Borax and continues to supply nearly half the world’s borates.

In 1988, just over 20 years after the acquisition of U.S. Borax by Rio Tinto Group, the Boraxo, Borateem, and 20-Mule Team product lines were sold to Dial Corporation by U.S. Borax.

Today, the Francis Marion Smith Park continues to be utilized on land donated by the Smiths from their former estate. It is on Park Boulevard in Oakland. Smith Mountain, a peak in the Amargosa Range of Death Valley, is also named in his honor. The Western Railroad Museum at Rio Vista Junction on State Route 12 in Fairfield/Suisun City, California, includes an archives wing named for him. The museum also includes several operating streetcars and transbay trains that operated on the Key System lines in Oakland and adjacent cities on the east side of San Francisco Bay.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Also See:

20-Mule-Teams in Death Valley Borax Mining in Death Valley

Characters of Early Death Valley

The Pacific Coast Borax Company

See Sources.